Media Release

Isentia Leadership Index reveals two distinct CEO styles

Isentia’s second edition of its Leadership Index has revealed two distinct styles of leadership

As disruption becomes the new norm, we were curious about what the faces of that disruption looks like right now. Is it a fully realised concept in media coverage, or has it become a way for brands and leaders to position themselves, rather than being or driving disruption?

DISRUPT: (verb dis·rupt \dis-ˈrəpt\) to cause (something) to be unable to continue in the normal way; to interrupt the normal progress or activity of (something)

‘The face of disruption’ takes a look at who the disruptors are across ANZ and Asia, the common themes, those who hold a ‘celebrity like’ status and what observations can be made as these leaders are seen to evangelise change and drive results.

Since edition one, we’ve also updated our benchmark analysis of CEO profiles and media trends of Australia and New Zealand’s top 150 companies and examine the shifts as well as newcomers to the group.

Download a copy of the report here or if you would like to discuss the report further, get in touch with us today!

This is the “wpengine” admin user that our staff uses to gain access to your admin area to provide support and troubleshooting. It can only be accessed by a button in our secure log that auto generates a password and dumps that password after the staff member has logged in. We have taken extreme measures to ensure that our own user is not going to be misused to harm any of our clients sites.

26th March 2019

As well as updating its analysis of CEOs in Australia and New Zealand’s top 150 companies, Isentia explored the characteristics of Australian leadership through the lens of disruption. The top 150 companies were derived from a combined list of the ASX50, the NZX50, the 2018 IBIS World Top 500 companies published by The Australian Financial Review and Deloitte’s Top 200 data in New Zealand.

Isentia’s Chief Insights Officer, Khali Sakkas, says observations around the behaviour and portrayal of disruptive leaders are key in understanding modern businesses.

“Often in business we focus on measuring performance solely with financial metrics. However, this approach fails to recognise the impact of leadership trends and values,” Sakkas says. “We included a study of disruptive figures because in the current business climate, every single industry is seeing disruption, whether from technology developments or heightened customer expectations.

“Assessing disruptive personalities adds another layer of insight into the leadership of Australian business. No single individual featured in both the top 25 CEOs and the top five disruptive leaders. What we’re noticing is two distinct styles of leadership.

“Traditional CEOs are typically required to be risk averse, answering to shareholders and board members. On the other hand, the new generation of disruptors are usually undertaking a potential risk, yet their creativity can have a huge payoff.”

To identify disruptive leaders, Isentia used its extensive media database to search for varying forms of the word “disrupt” in combination with leaders’ names. The most mentioned disruptors were global business leaders with celebrity status including Tesla’s Elon Musk and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Positive characteristics of this group included “ambitious” and “charismatic” while “erratic” and “impulsive” were listed as negative attributes. A significant 46 per cent of coverage regarding these individuals focused on their personal life, wealth and behaviour.

Coverage of Australian disruptors was often focused on business being disrupted, rather than the individual responsible for the change. Personalities were positioned as decisive and innovative leaders, with minimal negative attributes. The number one disruptive leader was Telstra CEO Andy Penn, who has led the telecommunications giant through a pivotal transformative period from mid-2018. With the rollout of the NBN, Telstra has required strong leadership to navigate the substantial changes to its business.

Penn exhibits the three most common traits of a disruptive leader: the ability to provide guidance in the face of circumstances outside of the business’ control, a focus on keeping technology front-of-mind in decision-making, and an aptitude for agile, flexible and forward-thinking ideas.

Isentia analysed more than 50,000 media items aired or published between 1 October and 31 December 2018 to provide an understanding of Australia and New Zealand’s top 150 companies. As in the first Leadership Index released in November, the CEO profiles and media trends of these businesses were assessed to reveal the top 25 CEOs. The three main factors that were evaluated were public perception, employee approval and financial performance.

Of the 150 companies assessed, the top 50 alone were mentioned in more than 700,000 media items. However, on average, the top CEOs were only present in nine per cent of their company’s coverage. BHP CEO, Andrew Mackenzie, retained his position as the number one leader in the final quarter of 2018.

The Isentia Leadership Index is designed to provide a benchmark to compare leadership profiles over time, highlighting key trends and figures as they shift each year.

“Broadening our report to include a study of disruption has really enriched our understanding of Australian leadership. It will be interesting to see which style of leadership becomes more prevalent in the coming years, as we continue to undertake our Leadership Index. Suggestions for other research topics are always welcome,” Sakkas says.

-ENDS-

For more information, please contact:

Sophie Willis

Howorth Communications

sophie@howorth.com.au 0458 111 948

Isentia’s second edition of its Leadership Index has revealed two distinct styles of leadership

Every stakeholder relationship is different, and managing them effectively takes more than a one-size-fits-all approach.

From campaign planning to long-term engagement, having the right tools and strategy in place can make the difference between missed connections and meaningful impact.

A practical guide to tailored stakeholder management, offering strategies and tools to identify, map, and nurture relationships.

At our Taking Back Trust panel, speakers didn’t just agree that public confidence in media, institutions and messaging is shifting. They challenged long-held assumptions about how trust is earned in the first place.

Some framed the current moment as a genuine “trust crisis”. Others saw something more layered, a redefinition of who and what audiences choose to believe. As Monica Attard OAM pointed out, trust in journalism today is shaped by whether audiences feel respected. Not spun, not lied to, not taken for a ride. When news feels ideologically loaded or out of step with what people know to be true, trust quickly erodes.

The panel made it clear that trust isn’t built through repetition. It’s forged through clarity, transparency and context. Two pillars stood out: accessibility and personal relevance. Trust is no longer just about the messenger. It’s about whether the message feels honest, and whether it meets people where they are.

The rise of polarised news and fragmented information ecosystems hasn’t just affected the public. It has reshaped how media outlets themselves think about trust. As John McDuling of Capital Brief noted, earning trust today requires more than getting the story right. It demands openness about how the story was made.

That means being transparent about where information comes from, clearly attributing sources, and acknowledging mistakes. “Correcting errors is a strength, not a weakness,” he said. Vague or thinly sourced reporting, once more easily accepted, no longer cuts through. Trust is now built through precision, accountability, and the willingness to show your work.

Much of the discussion circled back to how audiences are evolving. Younger generations aren’t just consuming news differently, they’re questioning the idea of shared truth altogether. There’s a growing scepticism toward objectivity as a fixed standard. Instead, content that reflects personal experiences and values tends to resonate more.

This shift is most visible on platforms like TikTok and Reddit, which panellists noted as primary news sources for many younger users. People now engage with information on their own terms, often picking up snippets in their feed before diving deeper through Google searches or podcasts. According to Dr Lisa Portolan, this more autonomous style of consumption is changing how trust is formed, and how communication needs to adapt.

She highlighted a broader transformation in the nature of trust itself. For most of human history, trust was built locally. Institutional trust, in government, media, or politics, only became dominant in the last few centuries. Now, technology is redistributing that trust again. People are more likely to believe a peer or content creator than a traditional source. That shift, Portolan said, represents both a degradation of institutional trust and a redefinition of what trust looks like in a decentralised environment.

From a communications perspective, it also means navigating synthetic and AI-driven research with care. When organisations don’t fully understand their audiences, there’s a risk of being misled by artificial signals. The solution, as the panel noted, lies in truly knowing your audience, not just where they are, but how they decide who and what to trust.

If there was one issue that united the panel, it was the urgency around artificial intelligence.

The conversation went beyond newsroom tools or job losses. The focus was trust. Panellists raised concerns about bias in training data, a lack of transparency from AI providers, and the risk of narrowing information loops shaped by commercial deals.

Monica Attard spoke about the dangers of closed systems, where the same sources are surfaced repeatedly, and the need to keep human values at the centre. Relying on technology alone, she said, won’t solve trust issues.

The panel returned to attribution as a key differentiator. As John McDuling noted, one way to stand apart from AI-generated content is to clearly link to original sources, especially those outside commercial LLM training sets. He wasn’t convinced AI would help build trust, at least not yet. These tools always give an answer, even when it’s wrong.

He compared the emerging response to an organic food movement. “You can trust this was generated by humans.” In a more artificial information environment, that may become the most important signal of all.

There’s no silver bullet. But across the board, the panel pointed to consistency, transparency, and nuance as essential tools, even when messages are uncomfortable or contested.

Sometimes trust isn’t about getting everything right. It’s about showing up, being clear about your limits, and staying open to scrutiny.

Ngaire Crawford challenged common assumptions about media literacy, pointing out that the problem isn’t confined to young people. In fact, older audiences are often more vulnerable to misinformation because they struggle to navigate the digital information environments around them. The challenge, she said, is not just media literacy, but informational literacy, knowing how to critically assess and access trustworthy content.

From a communications perspective, that calls for vigilance. People want to feel in control of the information they consume. They want to research for themselves, but often can’t find what they need. That gap creates space for misinformation to thrive, and it raises new questions about how information will be surfaced by AI.

The answer? Over-communicate. Provide written sources, supporting detail, and longer-form content where possible. It’s not just about the message or the sound bite. It’s about making sure people have access to the information they need to come to their own conclusions.

At our Taking Back Trust panel, speakers didn’t just agree that public confidence in media, institutions and messaging is shifting. They challenged long-held assumptions about how trust is earned in the first place. Some framed the current moment as a genuine “trust crisis”. Others saw something more layered, a redefinition of who and what audiences […]

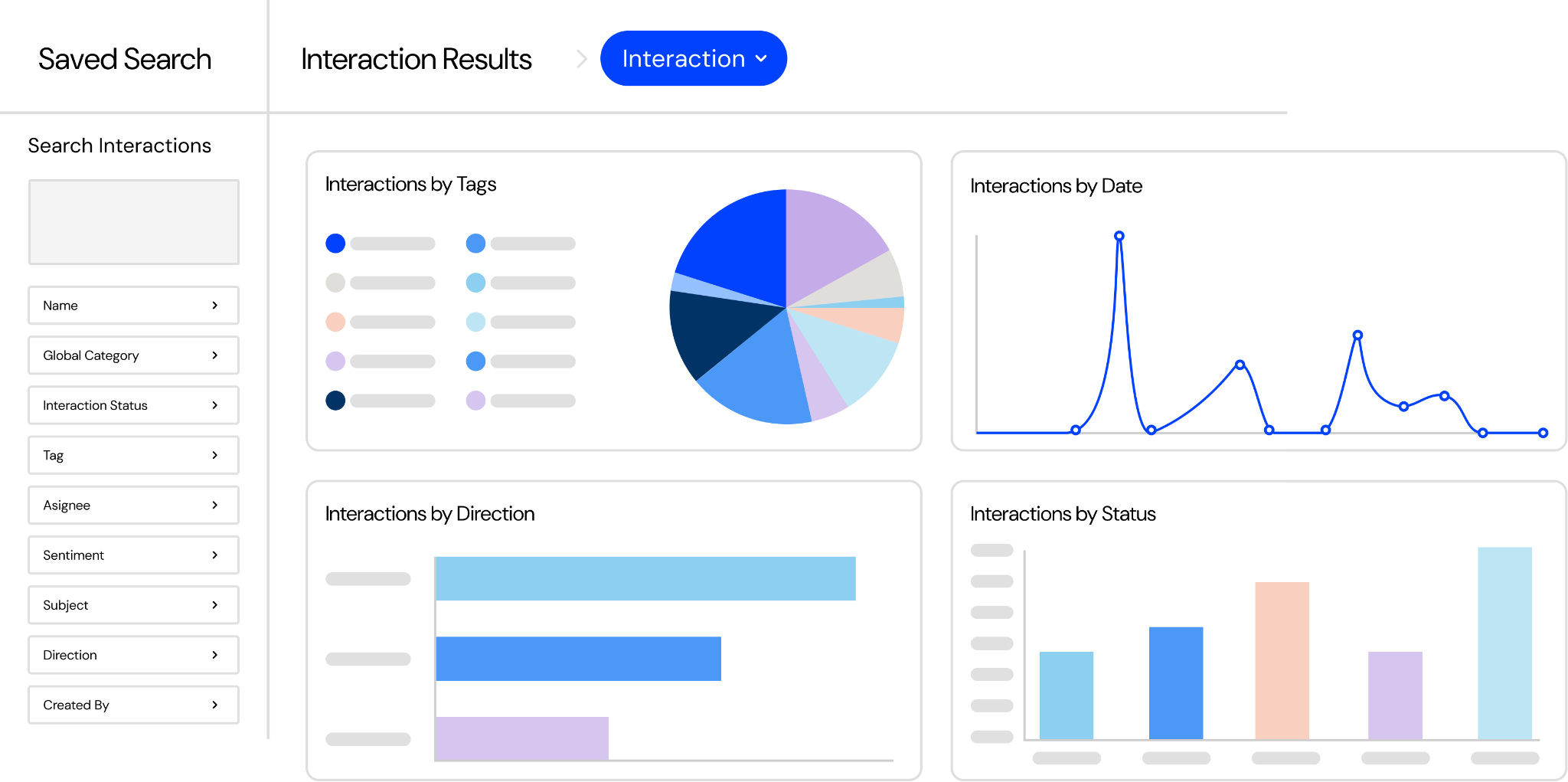

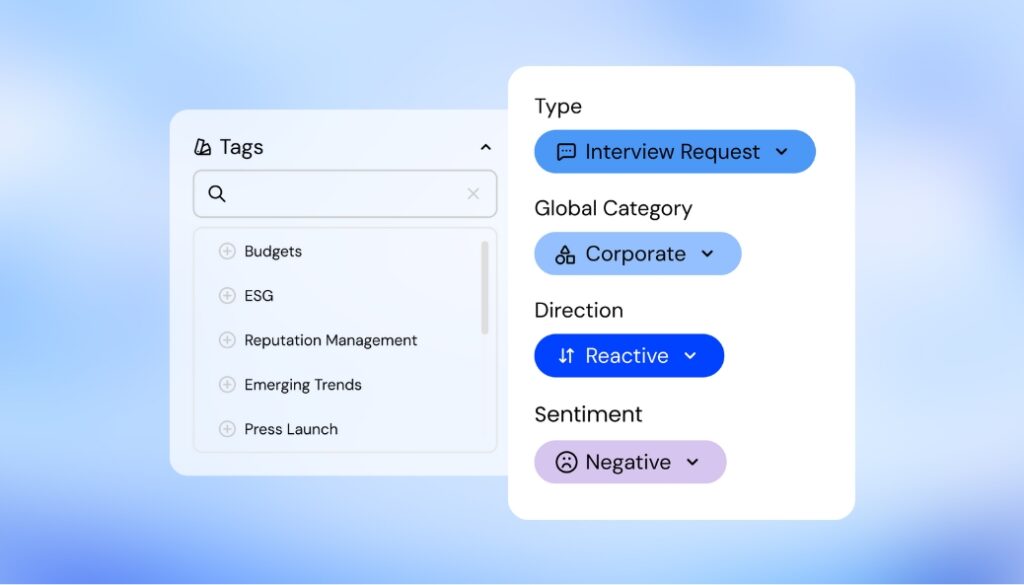

Across the communications landscape, teams are being asked to do more with less, while staying aligned, responsive and compliant in the face of complex and often shifting stakeholder demands. In that environment, how we track, report and manage our relationships really matters.

In too many organisations, relationship management is still built around tools designed for customer sales. CRM systems, built for structured pipelines and linear user journeys, have long been the default for managing contact databases. They work well for sales and customer service functions. But for communications professionals managing journalists, political offices, internal leaders and external advocates, these tools often fall short.

Stakeholder relationships don’t follow a straight line. They change depending on context, shaped by policy shifts, public sentiment, media narratives or crisis response. A stakeholder may be supportive one week and critical the next. They often hold more than one role, and their influence doesn’t fit neatly into a funnel or metric.

Managing these relationships requires more than contact management. It requires context. The ability to see not just who you spoke to, but why, and what happened next. Communications teams need shared visibility across issues and departments. As reporting expectations grow, that information must be searchable, secure and aligned with wider organisational goals.

What’s often missing is infrastructure. Without the right systems, strategic relationship management becomes fragmented or reactive. Sometimes it becomes invisible altogether.

This is where Stakeholder Relationship Management (SRM) enters the conversation. Not as a new acronym, but as a different way of thinking about influence.

At Isentia, we’ve seen how a purpose-built SRM platform can help communications teams navigate complexity more confidently. Ours offers a secure, centralised space to log and track every interaction, whether it’s a media enquiry, a ministerial meeting, or a community update, and link it to your team’s broader communications activity.

The aim isn’t to automate relationships. It’s to make them easier to manage, measure and maintain. It’s about creating internal coordination before the external message goes out.

Because in today’s communications environment, stakeholder engagement is not just a support function. It is a strategic capability.

Interested in how other teams are managing their stakeholder relationships? Get in touch at nbt@isentia.com or submit an enquiry.

" ["post_title"]=> string(52) "SRM vs CRM: which is right for PR & Comms teams?" ["post_excerpt"]=> string(0) "" ["post_status"]=> string(7) "publish" ["comment_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["ping_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["post_password"]=> string(0) "" ["post_name"]=> string(44) "srm-vs-crm-which-is-right-for-pr-comms-teams" ["to_ping"]=> string(0) "" ["pinged"]=> string(0) "" ["post_modified"]=> string(19) "2025-06-02 02:39:21" ["post_modified_gmt"]=> string(19) "2025-06-02 02:39:21" ["post_content_filtered"]=> string(0) "" ["post_parent"]=> int(0) ["guid"]=> string(32) "https://www.isentia.com/?p=40160" ["menu_order"]=> int(0) ["post_type"]=> string(4) "post" ["post_mime_type"]=> string(0) "" ["comment_count"]=> string(1) "0" ["filter"]=> string(3) "raw" }Across the communications landscape, teams are being asked to do more with less, while staying aligned, responsive and compliant in the face of complex and often shifting stakeholder demands. In that environment, how we track, report and manage our relationships really matters. In too many organisations, relationship management is still built around tools designed for […]

Get in touch or request a demo.