Blog

Analysing Australia’s higher education landscape in 2025

A deep dive into how global audiences perceive Australian higher education and the university sector with a spotlight on the SEA region.

In a time where there is an enormous amount of information, we focus on the role traditional and social media have on public opinion through media and reputation analysis across all forms of media. And how it looks through a media lens.

In this blog, we discuss COVID-19 communication across various case studies and talk in depth about the 3 pillars of good communication during COVID-19.

You can also watch Isentia’a Ngaire Crawford discuss communicating through COVID-19 here

The clarity of information is incredibly important from the outset.

For example, the New Zealand government and its COVID-19 response team have provided clear and consistent communication.

It’s easy to focus on the New Zealand Prime Minister and the effectiveness of her communication style. There are many things that get attributed to the Prime Minister because she is a woman: her empathy; how she manages conflict; how she defends her position, and; how she answers questions.

Beyond personal style, there was consistency to the NZ government’s communication that became part of everyday routines during level 4 lock down. The branding of communications was quick, and stayed consistent across all platforms for government information.The yellow striped logo and clear message to stay home, save lives, and the use of an alert level structure helped create a simple and effective message.

No communications response is perfect, and many elements of the NZ response haven’t kept up with the consistency in the detail, but the foundational message structure, visual brand and consistent delivery made it a framework that could withstand some of those inconsistencies.

In Australia, there was a slower start to a consistent communications approach. Although an initial concern, the Australian government stepped up and are now delivering clear messages needed to cut through in a crisis. The Prime Minister has provided an important sense of consistency by holding regular press conferences to update the nation directly. Not only have announcements for economic stimulus packages and public health precautions been clear, detailed and decisive, they’ve been broadly welcomed.

Effective communication during COVID-19 requires compassion and it comes from understanding your audience. Empathy and compassion are central to effective communication through COVID-19 across all sectors.

For a leader during a crisis, it’s crucial to be authentic, decisive and present. It’s important to develop trust long before a crisis hits, so audiences will accept you as an authoritative source.

COVID-19 has seen a shift to more empathetic leadership. Scott Morrison’s response has positioned him as more empathetic.He has shown the willingness to put his own customary views on hold including pledging to return the government’s budget to surplus.

The government has placed medical experts at the centre of the response. A national cabinet has been formed – chaired by Morrison but including state premiers from both sides of politics. There’s no red or blue teams, it’s team Australia. Listening to experts is working. And working together, across political parties, is working.

Across social media, discussions of mental health have increased more than 400% and references to anxiety have more than doubled. COVID-19 is also driving references to being unsafe, scared and isolated.

Throughout the crisis, we’ve seen strong reactions to organisations trying to take advantage of the situation, and to point out organisations or people that weren’t playing by the rules. Level 4 lock downs in New Zealand were incredibly strict on retail.

Compassion and social media do not always go hand in hand. Traditional media coverage often chastises social media for botting, conspiracy theories and misinformation, but social users have shown a hyper-awareness of mental health and safety.

The below images show social media users using a code to signal if someone needs help during lock down. While this might also be a performative gesture, it does set an expectation that abuse and toxic behaviours won’t be accepted.

An example indicative of different political and media environments, the Malaysian government, in particular, the Ministry for women, asks women not to nag their husband, and to consider using the tone of Doraemon, a cartoon cat from Japan (see image above).

There was also some communication suggesting that women are to dress nicely and wear makeup while isolated at home. Social media went crazy over this communication. It was quickly turned into a meme, caused a lot of backlash and created international attention that probably wasn’t intended.

Creativity and innovation has been a theme during COVID-19.

Communication is at the core of innovation. A lot of organisations are delivering information in ways they weren’t expecting, or connecting with customers in a new way. Knowing your audience and your communication style is important when being creative.

Although, with creativity comes over-saturation of information. Make sure your internal communications are on point, and your stakeholders/clients/customers know what’s going on, then start to look for those outward facing opportunities – it’s okay if there’s nothing to say right now.

The core trends that have resonated on social media are: social distancing; ways to stay connected; ways to keep kids entertained, and; mental and physical well being.

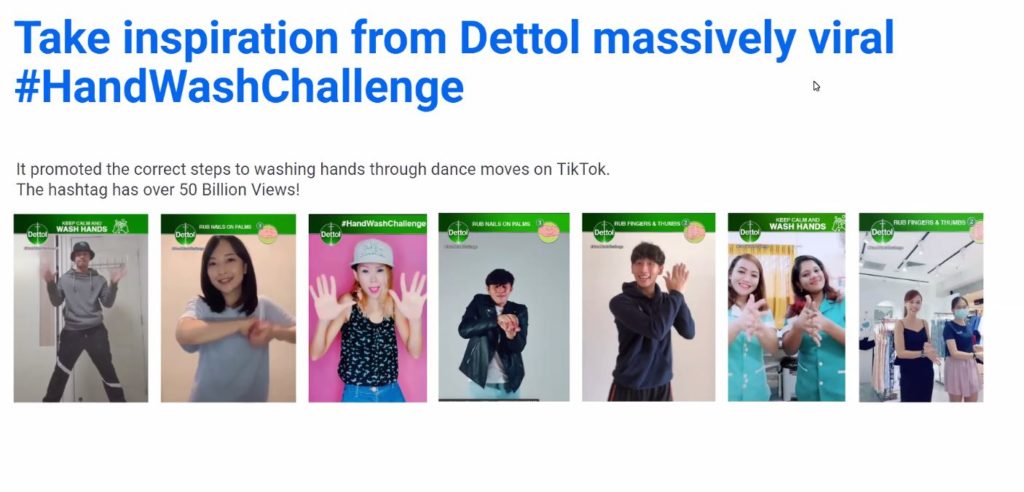

An interesting public health message example is Dettol’s hand washing challenge on TikTok, where people create dance moves around washing your hands. It’s communicating a known public health message in a creative way, to an audience that really wants to play by the rules and as a result, has over 50 billion views.

A crisis is a crisis for a reason, very few people default to best practice behaviours in a crisis – but planning, and planning based on what has previously worked can help mitigate some of this pressure.

The role of the media during COVID-19 hasn’t fundamentally changed as a trusted source. What has changed is that information is a far more crowded space, including content from traditional media sources, social media, influencers and the increased access to content internationally.

This means it’s important for your communication to be clear and consistent. Create a rhythm and content structure that makes your information easy to share and amplify. Check your crisis plans and consider how tied they are to a set of simple, core messages, or check what the process is to adapt and create messages in the first stage of a crisis.

It can be incredibly beneficial to get the foundations right, to gain trust, and create acceptance that all the information that may not be known yet.

For more information on how your organisation can be better prepared for a crisis, get in touch with us today.

Loren is an experienced marketing professional who translates data and insights using Isentia solutions into trends and research, bringing clients closer to the benefits of audience intelligence. Loren thrives on introducing the groundbreaking ways in which data and insights can help a brand or organisation, enabling them to exceed their strategic objectives and goals.

Get in touch or request a demo.